Not many people enjoy the existence of poverty. Some think it’s inevitable, others that tackling it is politically impossible. But for those with ambition, an end to poverty is a worthy enough goal. Naturally, the self-congratulation will be in full flow this weekend, as celebrities and world leaders gather in New York to launch their latest effort to do just that, in the form of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

But something will be missing in between the speeches and performances by the likes of Ed Sheeran, Beyoncé, Bill Gates and Meryl Streep. That thing is power. Because unless you understand that the poverty of some flows from the wealth and power of others, efforts to fight poverty will not truly work.

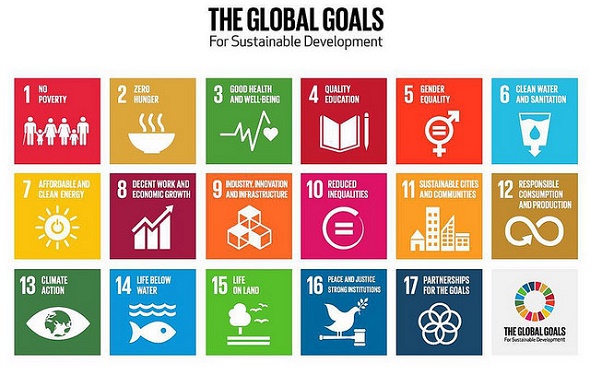

The SDGs consist of 17 objectives which aim to build a better planet – from eradicating hunger to building more sustainable cities. Each objective contains a number of targets which cover everything from having better public transport to helping artisanal fisherfolk get better access to markets.

The goals do represent the many dimensions of poverty – it isn’t simply about a certain number of dollars a day. While some targets are limited or problematic (‘preventing trade restrictions in agriculture’ could cover a multitude of sins) others are very good (‘encouraging local involvement in water management’ and ‘improving the incomes of small farmers’).

The real problem is that this wish-list comes with no historical background of how we got here, and no political strategy for how we get out. As such, it relies on a mixture of more market and more technically competent governments. There’s no sign that the economic model itself is broken – just that it needs some tuning.

Take one obvious gap: transnational corporations. They aren’t mentioned in the SDGs, yet the power of corporations is fundamental to the staggering levels of inequality which afflict the world, and are at the centre of an economic model quite prepared to burn the planet in its drive for ever more profit. It is impossible to realize the targets of the SDGs without tackling corporate power.

Nor is there any acknowledgment of colonial history, of slavery, of racism, of desperately unfair terms of trade, of structural adjustment policies which flushed dozens of countries’ economies down the drain only 30 years ago. Far from critiquing the control of the market, the SDGs exhort world leaders to ‘remove market distortions’ and ‘ensure the proper functioning of food commodity markets’.

The SDGs’ answer to ‘hunger’ is growing more food – despite the fact that we have more than enough food in the world to feed everyone. Technology plays a key role in the targets – for instance in the eradication of epidemics of HIV and malaria – but with no sign of how governments will improve the flow of knowledge around the world without breaking the ever more ferocious intellectual property regime that allows corporate giants to monopolize that knowledge. More foreign investment is encouraged, but without a framework for controlling that investment, how is it supposed to benefit the majority?

In short, power doesn’t exist in the SDGs. The chapter on inequality nowhere mentions that the problem of poverty is inseparable from the problem of super-wealth; that exploitation and the monopolization of resources by the few is the cause of poverty.

Of course, this lack of analysis isn’t accidental. In the world of fighting poverty, of ‘development’, corporations and the super-rich are no longer problems, but partners. How on earth will the SDGs be financed, especially since a global tax body has already been vetoed by rich countries 3 months ago? By big business, of course. With a captured public sector unable to fund the SDG promises, big business will happily come in, with state backing, to run healthcare and education, communications and transport, food and water. The market is the answer.

Perhaps it’s unfeasible to think that the UN could advocate such seemingly radical proposals as democratic control of the world’s resources? Actually, that doubt shows how far backwards we’ve gone. Because in the mid-1970s the UN adopted a policy which, while less detailed (mercifully, it fits on a few pages), laid out a far better analysis of the world’s problems, with a clearer set of solutions for moving forward.

It seems incredible now that the New International Economic Order (NIEO) was really UN policy, but it passed the General Assembly in May 1974 and was regarded as much too moderate by many campaigners of the time. The NIEO declared that ‘the remaining vestiges of alien and colonial domination, foreign occupation, racial discrimination, apartheid and neo-colonialism in all its forms continue to be among the greatest obstacles to… full emancipation and progress’. In an era when few people knew what a transnational corporation was, its recommendations included the ‘regulation and supervision of the activities of transnational corporations’, as well as radical reform of the global trade regime.

The world has changed and the NIEO is not a blueprint for a perfect planet. But it highlights the poverty of ‘development’ thinking, the pinnacle of which is represented by the SDGs. The answer to world poverty can’t be found among the development professional and celebrities in New York this weekend. Rather it will be found among the many thousands of activists, community organizations and social movements who are really confronting power in the world. Let’s join them.

source

.

More Stories

Navalny’s death used to hide western failures in Ukraine and their support for Israel’s genocide

Gifts from Gaza

Vulture capital circles over the corpse of Ukraine…